Introduction

I was working for a client on an Information Discovery project which gathered and evaluated data from a range of other platforms which were basically a Stovepipe Architecture, so we had brittle, incomplete data objects from a wide range of independent systems which all described the same business object. There were two goals: First, link the data into a common view - and second, highlight inconsistencies for data purification. So to say, it was a fledgling Master Data Management system.Stage 1: The Big Monolith

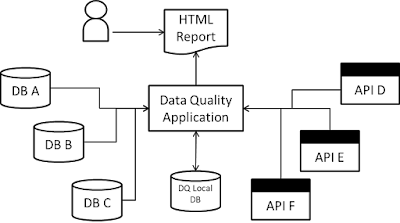

Although I knew about services, I never utilized them to their full potential. In stage one, my architecture looked something like this:The central application ran ETL processes, wrote the data to its own local database, then produced a static HTML report which was sent to users via mail.

The good news is that this monolithic application was already built on Clean Code principles, so although I had a monolith, working the code was easy and the solution flexible.

The solution was well received - indeed, too well. The HTML reports were sent to various managers, who in turn sent them to their employees, who in turn sent them to their colleagues who collaborated on the relevant cleanup tasks. This was both a data protection and consistency nightmare - I couldn't trace where the data went and who was working with which version. So I moved from an HTML report to server-side rendering within the application.

Stage 2: Large Components

My application became two - an ETL and a Rendering component, both built on the same database. I had solved the problem of inconsistent versions and access control:

But there was another issue: Not everyone needed the same data, and not everyone should see everything. There were different users with different needs. The Simplicity principle led me to client-side rendering: I would pass the data to the frontend, then let the user decide what they wanted to see.

Stage 3: The first REST API

I cut in a REST layer which would fetch the requested data from the backend based on URL parameters, then render these to the user on the browser:

This also solved another problem: I wouldn't need to re-create the report in the backend whenever I made changes to layout and arrangement. It enabled true Continuous Delivery - I could implement new representation-based user requests multiple times a day without having to do any changes to any data on the server. The cycle time was three to five relevant features - per day, and so the report grew.

Guess what happened next? People wanted to know what the actual data in the source system was. And that meant - there was more than one view.

Stage 4: Multiple Endpoints

Early attention to separable design and SOLID principles once again saved the day. I moved the Extraction Process out of the ETL application and into autonomous getter services:

This made my local database asynchronous with the data users might see, but this was a price everyone was willing to pay - it was enough if the report was updated daily, as long as people had access to un-purified raw data in real time. Another side benefit was that I pulled in pagination - increasing both performance and separability of the ETL process as a whole.

Loose coupling allowed me not only to have separate endpoints for each Getter, it allowed me to completely decouple each getter from a central point: I could scale!

As the application grew in business impact, more data sources were added and additional use cases came in. (To keep the picture simple, I'm not going to add these additional sources - just imagine there's many more).

Stage 5: Separate Use Cases

This modification was almost free - when the requirement came, I did it on a whim without even realizing what I had done until I saw the outcome:

Different user groups had different clients for different purposes. Each of the client needed only a subset of data, and that data was a subset of the available data - I could scale clients without even modifying anything in the core architecture!

And finally, we had network security concerns, so we had to pull everything apart. This was a freebie from a software perspective, but not a freebie from an infrastructure perspective: I separated the repositories and deployment process.

Stage 6: Decentralization

In this final stage, it was impossible to still call it "one application": I ended up with a distributed system with multiple servers, each of them hosting only a small set of functions which were fully encapsulated and could be created, provisioned, updated and maintained separately. In effect, each of my functions was a service running independently of its underlying infrastructure:

And yes, this representation omits a few of the infrastructure troubles I had, most notably, availability and discovery. The good news is that once I had this pattern, adding new services became a matter of minutes - Copy+Paste the infrastructure provisioning and write the few lines of code that did what I wanted to achieve.

Conclusion

As I like to say, "The monolith in people's heads dies last". Although I knew of microservices, I used to build them in a very monolithic way: Single source repository, single database and single deployment process. This monolithic approach kept infrastructure maintenance efforts low and reduced the complexity of maintaining system integrity.

At the same time, this monolithic approach made it difficult to separate concerns, pull in the necessary layers of abstraction to separate use cases, resulted in downtimes and a security nightmare: When you have access to the monolith, everything is fair game: Both availability and confidentiality are fairly easy to compromize. The FaaS approach I discovered for myself would allow me to maximize these two core goals of data security with no additional software complexity.

Thanks to tools like Gitlab, Puppet, Docker and Kubernetes, the infrastructure complexity of migrating from is manageable, and the benefits are worth it. And then, of course, there are clouds like AWS and Azure which make the FaaS transition almost effortless - when the code is ready.

Today, I would rather build 20 autonomous services with a handful of separate clients that I can maintain and update in seconds than a single monolith that causes me headaches on all levels, from infrastructure over testing all the way to fitness for user purpose.

This was my journey.

Your mileage may vary.