I get asked quite often some questions along the line, "How do we deal with work that's not related to the Sprint Goal?" The typical agile advice is that all work is part of the Product Backlog and treated as such and the work planned for the Sprint is part of the Sprint Goal.In general, I would not recommend this as a default approach. I often advise the use of Planning Buffers.

Where does the time go?

Teams working in established organizations on legacy systems often find that the amount of work which doesn't advance the product makes up a significant portion of their time. Consequently, when they show up in a Sprint Review, the results tend to go into one of two directions:

Either, the team will have focused on new development, angering existing users why nobody tackled known problems - or, the team will have focused on improving legacy quality - angering sponsor why the team is making so little progress. Well, there's a middle ground: angering everyone equally.

In any case, this is not a winning proposition, and it's also bad for decision making.

Create transparency

A core tenet of knowledge work is transparency. That which isn't made explicit, is invisible.

This isn't much of an issue when we're talking about 2-5% of the team member's capacity. Nobody notices, because that's just standard deviation.

It becomes a major issue when it affects major portions of the work, from like a quarter upwards of a team's capacity.

Eventually, someone will start asking questions about team performance, and the team, despite doing their best, will end up in the defense. That is evitable by being transparent early on.

Avoid: Backlog clutter

Many teams resort to putting placeholders into their backlog, like "Bugfix", "Retest", "Maintenance" and assigning a more or less haphazard number of Story Points to these items.

As the Sprint progresses, they will then either replace these placeholders with real items which represent the actual work being done - or worse: they'll just put everything under that item's umbrella.

Neither of these is a good idea, because arguably, one can ask how the team would trust in a plan containing items they know nothing about. And once the team can't trust it ... why would anyone else?

Avoid: Estimation madness

Another common, yet dangerous, practice, is to estimate these placeholder items, then re-estimate them at the end of the Sprint and use that as a baseline for the next Sprit.

Not only is such a practice a waste of time - it creates an extremely dangerous illusion of control. Just imagine that you've been estimating your bugfixing effort for the last 5 Sprints after each Sprint, and each estimate looks, in the books, as if it was 100% accurate.

And then, all of a sudden you encounter a major oomph: you're not meeting up to your Sprint Forecast, and management asks what's going on. Now try to explain why your current Sprint was completely mis-planned.

So then, if you're neither supposed to add clutter tickets, nor to estimate the Unknowable - then what's the alternative?

Introduce Capacity Buffers

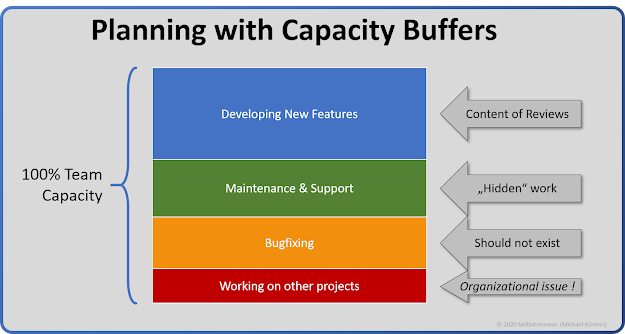

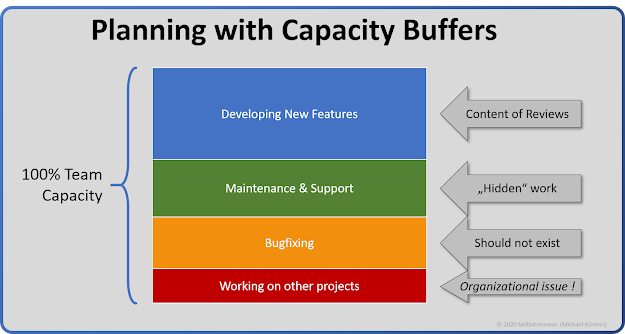

Once you've been working on a product for a while, you know which kinds of activities make up your day. I will just take these as an example: New feature development, Maintenance & Support, fixing bugs reported from UAT - and working on other projects.

I'm not saying that I advocate these are good ways to plan your day, just saying if this is your reality - accept it!

We can then allocate a rough budget of time (and therefore, of our develoment expenses) to each activity.

|

An example buffer allocation

|

Thus, we can use these buffers as a baseline for planning:

Buffer Planning

Product Owners can easily allocate capacity limits based on each buffer.

For example, 10% working on other projects, 25% UAT bugfixing and 25% maintenance work, which leaves 40% for development of new features.

This activity is extremely simple, and it's a business decision which requires absolutely no knowledge at all about how much work is really required or what that work is.

In our example, this would leave the team to plan their Sprint forecast on new feature development with 40% of their existing capacity.

As a side remark: every single buffer will drain your team's capacity severely, and each additional buffer makes it worse. A team operating on 3 or more buffers is almost incapacitated already.

These things are called "buffer" for a reason: we prefer to not use them, but we plan on having to use them.

Sprint & PI Planning with Buffers

During the planning session, we entirely ignore the buffers, and all buffered work, because there is nothing we can do about it. We don't estimate our buffers, and we don't put anything into the Sprint Backlog in its place. We only consider the buffer as a "black box" that drains team capacity. So, if under perfect circumstances, we would be able to do 5 Backlog items in a week, our 60% allocated buffer would indicate that we can only manage 2 items.

Since we do, however, know that we have buffer, we can plan further top value, prioritized backlog items that do contribute to our team's goal, but we would plan them in a way that their planned completion would work out even when we need to consume our entire buffer.

So, for example: if our Team Goal would be met after 5 backlog items, we could announce a completion date in 3 Sprints, since our buffers indicate that we're most likely not going to make it in 1 Sprint.

Enabling management decisions

At the same time, management learns that this team isn't going at full speed, and intervention may be required to increase the team's velocity. It also creates transparency how much "bad money" we have to spend, without placing blame on anyone. It's just work that needs to be done, due to the processes and systems we have in place.

If management would like "more bang for the buck", they have some levers to pull: invest into a new technology system that's easier to maintain, drive sustainability, or get rid of parallel work. None of these are team decisions, and all of them require people outside the team to make a call.

Buffer Management

The prime directive of activity buffers is to eliminate them.

First things first, these kinds of buffer allocations make a problem transparent - they're not a solution! As such, the prime directive of activity buffers is to eliminate them. and the first step to that is shrinking them. Unfortunately, this typically requires additional, predictable, work done by the team, which should then find its way into the Product Backlog to be appropriately prioritized.

Buffers and the Constraint

If you're a proponent of the Theory of Constraints, you will realize that the Capacity buffers proposed in this article have little relationship to the Constraint. Technically, we only need to think about capacity buffers in terms of the Constraint. This means that if for example, testing is our Constraint, Application Maintenance doesn't even require a buffer - because the efforts thereof will not affect testing!

This, however, reuires you to understand and actively manage your Constraint, so it's an advanced exercise - not recommended for beginners.

Consuming buffers

As soon as any activity related to the buffer becomes known, we add it to the Sprint Backlog. We do not estimate it. We just work it off, and keep track of how much time we're spending on it. Until we break the buffer limit, there is no problem. We're fine.

We don't "re-allocate" buffers to other work. For example, we don't shift maintenance into bugfixing or feature delivery into maintenance. Instead, we leave buffer un-consumed and always do the highest priority work, aiming to not consume a buffer at all.

Buffer breach

If a single buffer is breached, we need to have a discussion whether our team's goal is still realistic. While this would usually be the case in case of multiple buffers, there are also cases where buffers are already tight and the first breach is a sufficiently clear warning sign.

Buffer breaches need to be discussed with the entire team, that is, including the Product Owner. If the team's goal is shot, that should be communicated early.

Buffer sizing

As a first measure, we should try to find buffer sizes that are adequate, both from a business and technical perspective. Our buffers should not be so big that we have no capacity left for development, and they shouldn't be so small that we can't live up to our own commitment to quality.

Our first choice of buffers will be guesswork, and we can quickly adjust the sizing based on historic data. A simple question in the Retrospective, "Were buffers too small or big?" would suffice.

Buffer causes

Like mentioned above, buffers make a problem visible, they aren't a solution! And buffers themselves are a problem, because they steal the team's performance!

Both teams and management should align on the total impact of a buffer and discuss whether these buffers are acceptable, sensible or desirable. These discussions could go any direction.

DevOps teams operating highly experimental technology have good reasons to plan large maintenance buffers.

Large buffers allocated to "other work" indicate an institutional problem, and need to be dealt with on a management level.

Rework buffers, and bugfixing is a kind of rework, indicate technical debt. I have seen teams spend upwards of 70% of their capacity on rework - and that indicates a technology which is probably better to decommission than to pursue.

Buffer elimination

The primary objective of buffer management is to eliminate the buffers, Since buffers tend to be imposed upon the team by their environment, it's imperative to provide transparent feedback to the environment about the root cause and impact of these buffers.

Some buffers can be eliminated with something as simple as a decision, whereas others will take significant investments of time and money to eliminate. For such buffers, it tends to be a good idea to set reduction goals.

For example, reducing "bugfixing" in our case above from 25% to 10% by improving the system's quality would increase the team's delivery capacity from 40% to 55% - we nearly double the team's performance by cutting down on the need for bugfixing - which creates an easy-to-understand, measurable business case!

Now, let me talk some numbers to conclude this article.

The case against buffers

Imagine you have a team whose salary and other expenses are $20000 per Sprint.

A 10% buffer (the minimum at which I'd advise using them) would mean not only that you're spending $2000 on buffers, but also that you're only getting $18000 worth of new product for every $20k spent!

Now, let's take a look at the case of a typical team progressing from a Legacy Project to Agile Development:

Twice the work ...

Your team has 50% buffers. That means, you're spending $10k per Sprint on things that don't increase your company's value - plus it means your team is delivering value at half the rate they could!

Developers working without buffers, would be spending $20k to build (at least) $20k in equity, while your team would be spending $20k to build $10k in equity. That means, you would have to work twice as hard to deliver as positive business case!

Every percent of buffer you can eliminate reduces the stress on development teams, while increasing shareholder equity proprtionally!

And now let's make that extreme.

Fatal buffers

Once your buffer is in the area of 75% or higher, you're killing yourself!

Such a team is only able to deliver a quarter of the value they would need to deliver in order to build equity!

In such a scenario, tasking one team with 100% buffer work, and setting up another team to de-commission the entire technical garbage you're dealing with is probably better for the business than writing a single additional line of code in the current system.

Please note again: the problem isn't the capacity buffer. The problem is your process and technology!

High Performance: No Buffers

High Performance teams do not tolerate any capacity buffers to drain their productivity, and they eliminate all routine activity that stops them from pursuing their higher-ordered goal of maximizing business value creation. As such, the optimal Capacity buffer size is Zero.

Use buffers on your journey to high performance, to start the right discussion about "Why" you're seeing the need for buffers, and the be ruthless in bulldozing your way to get rid of them.