People working in bigger companies often do things which don't really seem to make sense when looking at the big picture. And yet, they're often pretty reasonable in their choices. They are intuitively following basic psychological and economical principles. Let's explore.

The economy of needs, wants and incentives

Let's start out at the detail level of the individual. Each person has needs:

The need pyramid

Maslow's hierarchies of Needs, sometimes also called "Maslow's pyramid" is built on the theory that every human being has needs, and these needs follow a hierarchical order. This picture is already a simplification, more comprehensive models are abundant on the Internet.

While each person has the same types of needs and the pyramid is the same, the level at which these needs are considered "satisfied" widely differ.

One person might feel basically satisfied with a bowl of rice and a few cups of water, whereas another person requires a more special diet to sustain. These are the basic needs, which must be met to ensure survival. People whose basic needs aren't met will not have a mind to think about other things, their primary concern will always be meeting these needs.

Once people are satisfied at the basis, they care for psychological needs - family, social ties, being accepted and valued.

With such a firm foundation starts the restless search for meaning in life - developing one's personality, being creative, pursuing a cause. At this level, people look for transcendency.

Dan Pink mentions this in his book, "Drive" - without fully realizing that it's not just that the money must be off the table, but all basic and psychological needs. People who feel threatened for their physiological well-being or social status aren't looking for transcendence, so in order to set up an organization where people go to look for a higher purpose, there's a lot of groundwork to be done in taking care of people first.

From "Need" to "Want"

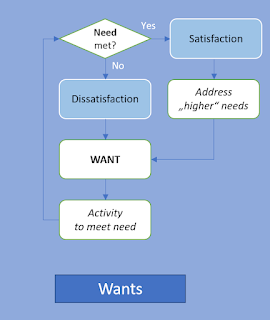

Unmet needs cause dissatisfaction with the status quo. This is also true for the future, because people think ahead.

We build our needs pyramid from the bottom, and whenever a lower-levelled needs turns to an unmet status, everything on top of that need gets out of focus. A starving person doesn't care for appreciation (many artists can tell that story.) A bullied person won't feel the office aesthetics. And so on. So, when a person has an unmet need, they want something, and action is required to satisfy the need (although it could be a different actor to serve the person in need.)

There are a lot of intermediary Wants - for example, money can be used to meet all kinds of need. When a person is hungry, they want money to buy food. Or drink. Or to pay the rent. Once basic needs are satisfied, they might invest that money to buy a token of wealth that meets their need for social recognition. And so on.

Other intermediary Wants, such as a promotion, could be more complex: Is it about the job title for prestige, is it about the presumed job security, about the additional pay, is it to rise the ranks to improve status? Maybe all - maybe only some.

Or maybe the idea that the Want satisfies the need is an illusion?

The key takeaway here is - if there's a need, there is a want. Ignoring the underlying need will render attempts to satisfying a Want ineffective.

Incentives

Incentives don't directly affect needs. They work because they trigger (both positive and negative) wants: things the individual wants, in order to meet needs - and things the individual wants to avoid, in order to not have needs unmet.

An incentive always stimulates at least one Want.

Positive incentives

Positive incentives give people the ability to satisfy their needs if they conduct a certain action. The most common form of positive incentive is, "Do your job, get your paycheck." Even a simple "thumbs up" from a coworker can be an incentive to try and go the extra mile.

The strength of an incentive depends much less on the nominal amount of incentivization - much rather, it depends on the level of unmet need. For example, you won't entice Donald Trump with a Thumbs Up, but the new team member who's not certain of their position in the team yet may be willing to go great lengths to finally get the lead developer to nod in agreement of something.

Negative incentives

Just like positive incentives, we can find ourselves subject to negative incentives. For example, the negative incentive "skip dinner" attached to overtime plays on our Want to not be hungry.

In society, we use negative incentives to deter certain behaviours, such as fines (which affect people differently, depending on their wealth.)

Explicitly phrasing negative incentives helps people discover which courses of actions are desirable and which are undesirable.

Managers quickly forget that there are almost always some negative incentives attached to their words: Even asking for a trivial thing might leads to the person feeling their status in front of their peers is diminished - a negative incentive, which people try to avoid.

The incentive economy

An economy is defined by wealth - in this case, we define "wealth" as satisfied needs.

In the case of incentives, we're dealing with promises of future wealth, hence, a value proposition to the recipient of the incentive.

Passive incentives

"What could be a passive incentive?" - well, that's an incentive created by doing nothing. Taking an extreme example, when a police officer continues munching donuts while a robber demands cash from the store owner, that's an incentive for the robber to commit further crimes. We see much less extreme examples in everyday's business world as managers fail to acknowledge the successes and contribution of their teams, incentivizing individuals to either cut down on performance (if stress is affecting their basic needs) - or to start hunting for a better job.

The nefarious thing about passive incentives is that you literally don't need to do anything to trigger them.

Ineffective incentives

The next type of incentives we're looking at are ineffective incentives. A positive incentive which doesn't address a real Want is entirely ineffective - as are negative incentives which don't touch a relevant need. This is also the reason why a pay raise for a person who's already fully able to meet their basic and psychological needs is pretty ineffective, as Dan Pink in his work, "Drive" figured out.

The same is true for "fun activity at work" while people are worried about not being able to afford the rent: it affects a higher-levelled need while there are lower-levelled Wants.

We can try to manipulate people by suggesting that they do have a certain Want, a typical marketing strategy. Here we can quote Lincoln, "you can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can't fool all of the people all of the time." Eventually, people will realize that an incentive doesn't affect their needs, and they will ignore it. That is especially true for things often called "non-monetary incentives."

Likewise, when a person finds alternative ways of satisfying their Needs, the Want disappears, and the incentive fizzles. For example, new joiners will stop trying to achieve the recognition of their boss when they feel that the recognition of their peers means a lot more.

Hence, long-term incentives that have alternatives tend to be ineffective.

Perverse incentives

The final category of incentives are perverse incentives - these are different from the other categories.

When we try to incentivize an action, we usually try to do that to get a benefit from what they do. The term, "perverse incentive" comes into play when people have the Want, but the intended incentivized action isn't actually what people to in order to meet their need, and so they go to do undesirable things. "Cobra Farming" is a notorious example of a perverse incentive.

The problem with perverse incentives is that they work extremely well - just not in the way that the incentive-giver intended.

And there's another problem: Perverse incentives are extremely common in complex organizations where the relationship between cause and effect isn't clear.

Setting incentives without connecting to the recipient's reality often leads to perverted incentives.

Top managers coming up with broad-brushed incentivization schemes for people at shop floor level often realize this only when it's already too late.

Summary

Bringing it all together - we have to understand the real needs and how they can be met. We must learn to go beyond merely talking about our Wants.

From there, we must learn how to take care of each other's needs in effective ways.

That allows us to become explicit on the incentives that let us build "Win-Win" scenarios.

No comments:

Post a Comment